Want to get better grades?

Nope, I’m not ready yetGet free, full access to:

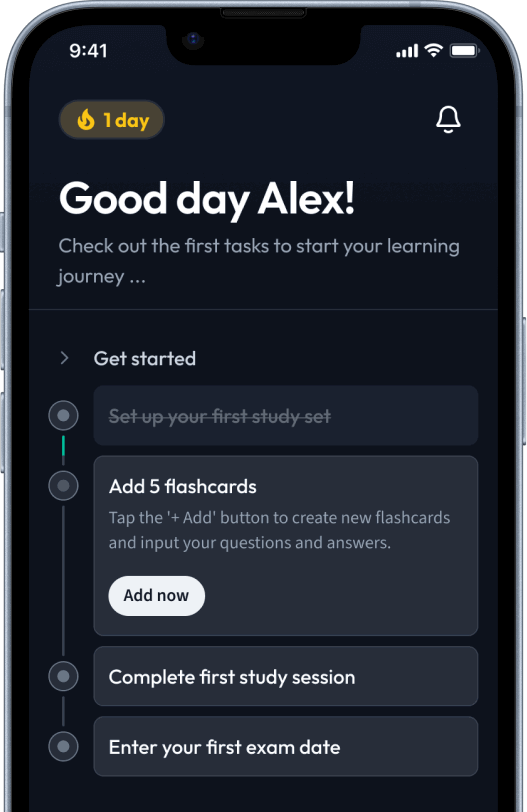

- Flashcards

- Notes

- Explanations

- Study Planner

- Textbook solutions

This period is one of revolutionaries and oppressive authoritarian regimes; of booming industrialization and radical changes in world order; of tradition clashing with modernity; of human suffering and human progress. Learning about Tsarist and Communist Russia, comparing the two, and seeing how they were similar is not just helpful in determining Russia’s place in the world today, but also in understanding the geopolitics of the last half-century.

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenThis period is one of revolutionaries and oppressive authoritarian regimes; of booming industrialization and radical changes in world order; of tradition clashing with modernity; of human suffering and human progress. Learning about Tsarist and Communist Russia, comparing the two, and seeing how they were similar is not just helpful in determining Russia’s place in the world today, but also in understanding the geopolitics of the last half-century.

The following is a high-level overview of the key events that occurred between the years 1855–1964. We will review them later in more depth.

1855–81: Rule of Tsar Alexander II

1856: Crimean War ends and Russia is defeated

1861: Enacted the emancipation of the serfs

1864: Reforms to the judicial system and local governments are introduced

1870: Elected town councils called Dumas were introduced

1881: Alexander II is assassinated by a group called the ‘People’s Will’, who wanted autocratic and Tsarist rule to come to an end

1881–94: Rule of Alexander III

1881: Alexander III pursued a policy of Russification

1889: Powers that the local governments held were revoked

1894: Alexander III dies from kidney failure

1894–1917: Rule of Tsar Nicholas II

1904: Russo-Japanese War breaks out

1905: On 22 January, Bloody Sunday occurs

1905: On 5 September, Russia surrendered and brought the Russo-Japanese war to the end signing the Treaty of Portsmouth

1905: On 30 October, Tsar Nicholas II implements the October Manifesto

1914: Nicholas II allied with Britain and France and entered Russia into the First World War

1915: On 6 September, Nicholas II personally headed the Imperial Army

1917: February Revolution occurred

1917: On 15 March, Tsar Nicholas abdicates and the provisional government is formed

1917: October Revolution occurred

1917–24: Bolshevik Consolidation of power and Vladimir Lenin’s leadership

1917: In December, the White Army begins to form and oppose the Bolsheviks, marking the start of the civil war

1918: On 3 March, Russia signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk to end Russia’s involvement in the First World War

1918: On 17 July, Nicholas II and his entire family were assassinated

1918: In September, the Red Terror begins

1921: On 18 March, Lenin implements the New Economic Policy

1924: On 21 January, Lenin dies

1924–53: Stalinist Dictatorship

1924: In December, Stalin advocates for ‘Socialism in One Country’

1929: Stalin announces the collectivisation of agriculture and the first Five Year Plan

1931: Collectivisation causes a massive famine in the USSR

1934: Sergei Kirov was assassinated, marking the beginning of the Great Terror

1939: The Nazi-Soviet Pact is signed on August

1941: On 21 June, Hitler invades the Soviet Union

1948: The USSR blockade East Berlin

1950: Sino-Soviet treaty is signed

1953: On 5 March, Stalin dies

1953–64: Nikita Khrushchev’s rule

1956: On 25 February, Khrushchev gives a secret speech denouncing Stalin

1956: In November, Khrushchev violently dispelled the Hungarian Uprising against Soviet hegemony in the country

1957: Khrushchev relaxed censorship laws, visited foreign countries, and implemented plans to raise the standard of living for the Russian people

1962: Cuban missile crisis raises tensions with the United States

1963: US and USSR agree to a partial nuclear test ban treaty

Consider the questions below as you learn about Tsarist and Communist Russia

The years 1855–94 cover the reign of Tsar Alexander II (who ruled from 1855 until his assassination in 1881) and his son, Tsar Alexander III (who ruled from 1881 until his death in 1894). During this period, Russia was a rapidly modernising, multi-ethnic nation whose elites established a belligerent foreign policy to legitimise itself domestically and preserve the system of autocracy that had existed for centuries.

In 1855, Russia was an autocracy (where absolute power over a state is held by one individual) ruled by the Tsar, who held the title, ‘Emperor and Autocrat of all Russia’. The Tsar was the head of the Orthodox Church, and his decrees were seen as God’s will.

Autocrat

A person with absolute power. In Russia, a Tsar would have absolute power.

Orthodox Church

A branch of the Christian church that has members from Eastern Europe to Eastern Africa (Russia, Greece, Ethiopia).

In 1855, Russia's economy was mainly rural, with over 90% of Russians living in villages. This meant it was economically behind the industrialised West, including Britain and France. The heavy agricultural focus of the Russian economy was a mainstay of Russian life until the rise of Stalin in 1924.

Reasons for Russia's slow economic development include:

Inhospitable terrain: much of Russia was barren and unsuitable for development.

Climate: Russia's extreme climate, especially the subzero temperatures, was problematic for agriculture and transport.

Size: Russia's size (1/6th of the world's land surface) made development expensive and challenging. In particular, communication across the empire was poor.

Serf-based economy: over 50% of Russians were serfs. Most serfs were subsistence farmers who grew just enough to survive on the land given to them by their landlords. The way the mirs (or village communities) managed the land meant that serfs had to farm communally, and had little opportunity to farm their private plots. Serfs often suffered from food shortages in bad harvests or winters.

Serfs

Peasant agricultural labourers who were tied to working on the estate of an aristocrat.

A nineteenth-century map of Russia

A nineteenth-century map of Russia

Russia was divided into the majority 'productive class' and minority 'non-productive class'. The productive class was mostly made up of serfs. It also included a small number of urban artisans, manufacturers, and merchants. The non-productive class consisted of the nobility, clergy, officials, and royal court. A 'middle class' did not exist in Russia in 1855. Some educated professionals (e.g. doctors and lawyers) formed the Russian intelligentsia, but they were usually the children of the nobility.

Of the 50% of Russians who were serfs, roughly half were 'state serfs'. These serfs paid taxes and rent. The rest of serfs were privately owned by members of the nobility. Serfs could be bought and sold, punished without trial, and were eligible for conscription into the army. Most serfs worked on the land in mirs, rural communes run by village elders. Peasants lived and worked in primitive conditions.

Conscription

A mandatory enlistment into the army.

Russia as an empire contained many different ethnic and national minorities. In the first national census of 1897, only 55% of Russian citizens identified as Russian nationals. The largest minority group was Ukrainians, at 22% of the population, followed by the Polish, at 8%. National minorities often retained their own culture, traditions, and language. They faced more restrictions and harsher treatment than Russian nationals. For example, Russian was the official language used in the government and civil service, and ethnic minorities were deterred from pursuing public service careers.

Under the rule of Tsar Alexander II, sweeping political, educational, judicial, and military reforms changed life in mid-nineteenth-century Russia. His rule effectively re-defined autocratic duty but also adhered to a phenomenon that historians call reform conservatism. This meant that the state resisted change, despite pursuing forward-looking goals that made the autocracy seem progressive.

Alexander II inherited from his father Nicholas I a country dispirited from the Crimean War (1853–56). Russia’s military was humiliated, its economy was on the brink of failing, its peasants were becoming increasingly dissenting, and the threat of war with foreign powers continued. Alexander II had realized that change was necessary and that Russia had to enter the modern age.

Portrait of Tsar Alexander II

Portrait of Tsar Alexander II

A new judicial system was created based on Western models of justice.

The military was transformed to include conscription for nobles and serfs alike. Modern weaponry and a new command structure were introduced; however, the military still faced problems of supply and leadership.

Primary and secondary schooling was extended to all people irrespective of class and gender.

Freedom of speech was introduced and press censorship was reduced. However, this led to scathing criticism of the ruling class and harsher censorship was re-introduced in 1870.

Perhaps Alexander II’s most radical reform was his emancipation of the serfs in 1861. He freed over 23 million Russians from serfdom. Although serfs became free citizens, they were still subjected to high taxes, restrictions on movement, and unfair distribution of fertile land.

Some key reasons for the emancipation of Serfs were:

The failure of Russia during the Crimean war.

Pressure from progressive nobles, who believed that a free population was key to Russia’s development.

The increase in peasant uprisings.

The reduction of state debts.

The Russian people had generally welcomed Alexander II as a symbol of hope and stability. However, his reforms also created opposition to his rule. As the reforms allowed people more freedoms, the public increasingly demanded great changes that would have threatened the security of Russia’s ruling elite. Radicals were not satisfied with the reforms as they felt that the nation remained essentially a serf owners’ state. On the 13th of March, 1881, Alexander II was assassinated.

Unlike his father, Tsar Alexander III believed strongly in the autocracy and adopted a more traditional ideology of autocratic religious legitimacy. His rule stands in stark contrast to that of his father. It was characterised by repression compared to the more liberal period under Alexander II. He viewed Russians with western education and the reformist nobles as guilty for the revolutionary movement that ultimately led to the assassination of his father. His main objective was to promote stability and ensure that the opposition to tsarism that had built up in the preceding years was controlled. Overall, his reign proved to be relatively secure for thirteen years until his death from a kidney disorder in 1894.

Portrait of Alexander III

Portrait of Alexander III

Alexander III centralised power and limited the democratic elements of the Russian government.

A policy of russification was enforced, which forced Russian culture and the Russian language on the ethnic minorities living in the empire.

Inheritance tax was introduced, which lessened the burden on peasants and instead shifted it to aristocrats.

Police were given more power over citizens, and their numbers were sharply increased.

Tsar Nicholas II was the last emperor of Russia, ruling from his father’s death in 1894 until his abdication in 1917. Much like his father, he believed in a vision of himself as a leader ordained by God who would restore patriarchal rule. As such, he refused to accept any concessions to his own absolute power. In general, he continued the policies of Alexander III, with an added emphasis on the modernisation of Russia. These policies had little positive impact, as Nicholas II had a limited grasp of politics; instead, they only made life harder for civilians and soldiers.

His regime was further complicated by a rapidly growing and indignant working class that demanded rights, and a middle class that demanded greater participation in government. This opposition was only made worse by the incompetence displayed in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05, and later in the First World War.

Tsar Nicholas II and his family in 1904

Tsar Nicholas II and his family in 1904

The 1905 Revolution, or the first Russian revolution, saw strikes, protests, peasant unrest, and military mutiny.

Long-term causes of the 1905 Revolution included:

Long-term economic hardship: newly emancipated peasants earned pitiful wages, were made to work in appalling conditions, and faced high taxation. Famine only exacerbated the hunger and difficulty that Russia's newly freed peasants endured.

Political discontent: ethnic minorities faced constant cultural repression due to the ongoing policy of ‘Russification’. The policy actively discriminated against minorities, banning them from serving in the Imperial Guard, limiting their access to education, and excluding them from voting. Working-class individuals resented the government for failing to protect their interests; strikes and labour unions were illegal. Moreover, intellectuals and some nobles criticized the Tsar for failing to modernise and democratise Russia.

Marxism was already popular in Russia at the turn of the twentieth century, and the Social Democrats (later split into the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks) wanted to overthrow the regime in order to give power to the working class.

Bolsheviks

The radical, far-left, revolutionary group that followed the beliefs of Karl Marx, specifically the working class overthrowing the existing capitalistic state in a revolution. The Bolsheviks followed Lenin and believed in a tight-knit, centralized party.

Short-term causes of the 1905 Revolution included:

The Russo-Japanese War: the humiliation of the Russian military in the Russo-Japanese War ended in the same year. Japanese negotiations to avoid war over territories in China were ignored by the tsarist regime because they believed that war would provide an opportunity to strengthen patriotism. However, Japanese forces proved to be vastly superior, and this made peasants and nobles alike question the competence of Tsar Nicholas II. The diversion of resources towards the war effort made domestic supplies of grain and oil even harder to come by.

Bloody Sunday: on 22 January 1905, Father Gapon led thousands of workers in a peaceful protest to deliver a petition to the Tsar. They called for changes to the working conditions of the lower classes. Imperial troops were sent to quell the demonstration. Hundreds were killed.

In the end, the revolution was short-lived, but it indicated the strength of the opposition to the autocratic rule that was building. The revolution did, however, bring about significant changes. On 17 October 1905, Nicholas II passed the October Manifesto. This was a constitutional reform that promised the creation of a State Duma, a legislative body elected by the people which would pass new laws. The manifesto granted the Russian people basic civil liberties, such as the freedom of speech, religion, and assembly. Nicholas II also appointed a cabinet headed by a Prime Minister, who would be directly accountable to him.

In 1917, Russia saw two tumultuous revolutions that would end centuries of tsarist rule and set the stage for the creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The first revolution occurred in February.

1917 February Revolution in Saint Petersburg

1917 February Revolution in Saint Petersburg

Long-term causes of the February 1917 Revolutions included:

An outdated political system: all the power was concentrated in the hands of Tsar Nicholas II. The Tsar feared power-sharing as it threatened his divine right to rule. Historian Scott Giltner argued that because of the Tsar’s disinterest in the working class, “Russia’s proletariat class was more radical than elsewhere”.

A decline in the prestige of the Tsardom: Russia had faced a series of embarrassing military defeats (in the Crimean War of 1853, in the Congress of Berlin over the Turks in 1880, in the Russo-Japanese War, and especially in the First World War, beginning in 1917). These national humiliations conflicted with Russia’s projection of itself as a great world power and brought economic devastation at home.

The rise of the intelligentsia: widening the access to education led to more people rejecting the current system of autocracy. The dissatisfaction of Russia’s peasant class was redirected to the government’s incompetency. The intelligentsia wanted major reforms, arguing that the October Manifesto failed to live up to its promises and was unwilling to accept minor compromises in the Duma.

Short-term causes of the February 1917 Revolutions included:

The First World War, which began in 1914. Estimates hold that more than two million Russian soldiers were killed during the war, in a crushing blow to the Russian empire. The Tsar made a myriad of critical errors in his management of the War, but perhaps the most significant was his decision to take direct command of Russia’s armed forces himself. This effectively tied the fate of the tsardom to the success or failure of the Imperial forces. Over the course of the War, enthusiasm for the Tsar evaporated, even among his natural supporters, the leaders of the army, the aristocrats in the Duma, and the progressive but non-radical parties.

By the end of the February Revolution, senior military leaders and prominent members of the Duma advised Nicholas II to abdicate. Members of the Duma then established a Provisional Government consisting of liberals, socialists, conservatives, and monarchists. Members of the working class began asserting a larger role in the governance of Russia. Despite these changes, the wealthy aristocrats of the provisional government entered into a power struggle with the less privileged members of the Provisional Government. Wartime chaos gained momentum in Russian cities, where individuals took it upon themselves to kill officials and military officers because they symbolised the old regime. This disorder, along with the need to fight in the War, weakened the government and the rest of Russia’s institutions.

This Revolution, led by Vladimir Lenin of the Bolsheviks, instigated a period of political and social change in which the Communist Party would control Russia until 1989.

Reasons for the 1917 October Revolution:

Weakness of the Provisional Government: the government was unelected and closely associated with the Tsar and the Duma. Issues of land ownership, inflation, overcrowding, working conditions, and food shortages were not addressed with any decisiveness or clarity. Similarly, because the representatives of the Provisional Government were unelected, ongoing political repression was blatant.

Strength of the Bolshevik Movement: Lenin’s ideologies were popular with the masses. Lenin declared a platform of ‘Peace, Bread, and Land’, in which he rejected the continuation of the Great War, and promised stability to the hungry and landless populace. Lenin asserted that as long as the Provisional Government continued to rule, these issues would remain unresolved; ministers only governed with the interests of their own class in mind, he asserted. He argued that there was no incentive for them to end the war because they profited off the war efforts. Similarly, they had no incentive to reform the land-holding system, which protected their own property rights while excluding the less privileged from ownership. It is in this spirit that Lenin demanded ‘All Power to the Soviets.’

By late October, Lenin persuaded his followers to take action against the provisional government. Leon Trotsky, Chairman and military chief of the Bolsheviks, organized the October Revolution which overthrew the government. The government offered little resistance.

On 17 July 1918, Nicholas II and his entire family were murdered by the Bolsheviks, putting an end to the Romanov dynasty and the tsardom that had existed for centuries.

Following the October Revolution, the Bolsheviks asserted control over Russia in a way that triggered fierce opposition. This led to a two-year civil war and foreign interventions. Triumphant, the Bolsheviks imposed their will by a ‘reign of terror’ under Lenin, which established a single-party authoritarian state. In 1919, the Bolshevik party was renamed the Communist Party. In 1922, the Soviet State became the Soviet Union.

The Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, broke away from Marx’s idea of communism, where the working-class would rise and spearhead a revolution. Instead, the Bolsheviks believed that an elite group of leaders needed to lead the Revolution. Indeed, the society that the Bolsheviks established was markedly different from the one that Marxist socialists had imagined in the nineteenth century. Instead of putting power in the hands of the workers, the Bolsheviks crushed opposition from peasants and soldiers who complained about the privileges of the Bolshevik elite.

Marx predicted that the state would diminish after a workers’ revolution, but the Bolshevik state only gained more power, albeit with broad support from the populace.

Vladimir Lenin’s legacy reverberated throughout the twentieth century. As the first leader of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Lenin laid the foundation for all future communist leaders. Lenin oversaw the creation of a communist state through a brutal civil war, founded the Communist International (Comintern), and instigated the New Economic Policy (NEP) to bolster the Soviet economy.

Lenin quickly made peace with the Germans, signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk which officially ended Russia’s participation in the First World War on 3 March 1918. Lenin then oversaw a bloody civil war against the ‘Whites’, who were a loosely associated group of armies united only by their resistance to Bolshevism. The side of the Bolsheviks was known as the ‘Reds’, led by Leon Trotsky. In the civil war, Lenin ordered the use of unsparing violence against the White Army but also against civilian peasants. This bloody campaign became known as the ‘Red Terror’, marking the start of the long history of violence from the communist party to suppress its opponents.

Vladimir Lenin in 1920

Vladimir Lenin in 1920

By 1922, Lenin was the unquestioned leader of a unified but devastated country. Shortly after consolidating power and establishing a single-party state, he suffered two strokes, passing on his power to Joseph Stalin. Lenin passed away on 21 January 1924.

Following Lenin's death in 1924, the Communist Party faced the problem of choosing a new leader. This created a power struggle between some of the Party’s members, but in the end, Joseph Stalin triumphed over Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev, Grigory Zinoviev, Nikolai Bukharin, and other prominent members of the Communist Party. In the years that led up to 1928, Stalin took advantage of several opportunities that arose to gain power and solidify his position as the indisputable leader of Soviet Russia.

Historian Stephen Kotkin characterizes Stalin as ‘a people person’ with ‘surpassing organisational abilities; a mammoth appetite for work; a strategic mind and an unscrupulousness that recalled his master teacher, Lenin.’

Stalin’s regime would prove to be one of the most ruthless in recorded history. Approximately 30 million people died from famine and state-mandated terror and millions more found themselves imprisoned in the terrifying Siberian labour camps known as gulags.

Joseph Stalin in 1937

Joseph Stalin in 1937

Stalin’s ideology changed over time to adapt to what was popular with the proletariat (Russia’s working-class). His ideology had direct, practical benefits for the people, which gave him broad support. For example, Stalin favoured ‘Socialism in One Country’, which focused the state’s efforts on domestic stability and peace over ‘permanent revolution’, which Trotsky and the left-wing of the Bolshevik party favoured (this would have led to continuous revolutionary upheaval and disorder abroad).

Stalin took advantage of the centralised government model. He ensured that all cultural associations, the clergy, and even the smallest social institutions were controlled by the party. This allowed him to consolidate what was almost complete control over the social life of the Russian people. Stalin also used his position of power to execute or exile any politician who threatened his absolute rule.

After the ‘purges’, in which vast numbers of the Communist Party and the Red Army were eliminated and the peasantry terrorized into obedience, Stalin ruled unchallenged until he died in 1953.

At the end of the 1920s, Stalin launched a myriad of radical economic policies that completely transformed the agricultural and industrial standing of the Soviet Union. Stalin eliminated private enterprise, market mechanisms, and concessions for foreign investment that the NEP had allowed for.

Stalin’s economic policy pointed broadly to one, overarching aim: to modernise the Soviet economy. This was to be achieved through collectivisation and industrialisation. Collectivisation refers to the policy of socialised agriculture that was implemented by the Soviet Union from 1929 onwards. Kolkhoz (collective farms) and Sovkhoz (state-owned farms) were founded to replace the individual farms owned by peasants. Roughly 25 million small farms were merged to create 200,000 kolkhozy. The Five Year Plans were a tool to accelerate industrialisation by strictly controlling, managing and measuring goals. The Five Year Plans detailed Soviet plans for growth over a set period and imposed industrial quotas on workers. The plans were set out by the Gosudarstvennyy Planovyy Komitet, or Gosplan, which was the state planning committee.

The Stalinist Economy was characterized by the costly process of industrialisation, the complete restructuring of the ancient system of peasant farming, and the total consolidation of Communist Party rule. The human suffering that this great upheaval brought about was staggering. However, it is undeniable that in the years between 1928-1940 Soviet Russia evolved from an agrarian economy into an industrialised one.

Khrushchev came to power in 1953, over other prominent politicians who had close ties to Stalin. Krushchev’s political ideology differed markedly from Stalinism, making him stand out as a reformer.

In 1956, Nikita Khrushchev delivered a ‘secret speech’ at the Twentieth Party Congress. In it, Khrushchev openly criticized Stalin and called for a return to Leninism. This speech made Khrushchev’s campaign of ‘de-Stalinization’ clear, as well as marking the beginning of a period of liberalisation known as the ‘Khrushchev Thaw’. Khrushchev strongly believed in communism and believed that the terror and suffering endured under Stalinism was an unfortunate mistake. As such, Khrushchev set out to create economic and social reforms that would allow for ‘socialism with a human face’.

Nikita Khrushchev in the Second World War

Nikita Khrushchev in the Second World War

‘De-Stalinization’

A series of political reforms pursued after the death of Stalin and Nikita Khrushchev's attempt to seize power.

The Communist Party was restructured along administrative lines, which shifted power away from Moscow to local authorities.

Legal reforms gave more protections to ordinary citizens and diminished the power of the secret police.

Khrushchev began the Virgin Lands Scheme in 1954, relocating thousands of workers to cultivate more than 70 million acres of land in Siberia. This scheme was largely unsuccessful as the quality of land was extremely poor.

Regional economic councils were established which had autonomy over setting industrial quotas.

Consumer goods were emphasised to increase the standard of living for Soviet citizens.

Khrushchev improved the USSR’s relationship with the US, establishing a policy of peaceful co-existence that culminated in the signing of the Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty in 1963. Unlike Stalin, he participated in numerous summits and travelled to Western countries. However, there were still moments of tension between the US and the USSR, as evidenced by the Cuban Missile Crisis which almost led the two powers into nuclear war.

Despite Khrushchev’s best efforts, his domestic policies suffered against the background of the financially debilitating Cold War. Often, he lacked the funds necessary to successfully carry out his plans. Moreover, his liberal attitude and his leniency towards the Soviet people threatened the authority of the Communist Party. In the end, his rivals launched a campaign to dismiss him in 1964, which was successful.

Here is a brief summary of the similarities and differences between Tsarist Russia and Communist Russia.

Similarities between Tsarist Russia and Communist Russia | Differences between Tsarist Russia and Communist Russia | |

Economy | Both were agrarian empires |

|

Politics | Political stability in both cases was dependent on the state’s ability to orchestrate a climate of fear and inertia. Both used terror tactics. Okhrana, the secret police, was formed under Alexander III to infiltrate revolutionary groups; it became even more active during Nicholas’ II rule, as the opposition was on its sharp rise. Lenin, meanwhile, launched the Red Terror to maintain his political power. His secret police, Cheka, would arrest members of other political parties, the Social Revolutionaries or the Mensheviks, and send them to gulags. Both used censorship as a form of maintaining power. Censorship was relaxed under Alexander II, resulting in an influx of opposition groups and revolutionary ideas. Alexander III tightened censorship, placing restrictions on books, banning public meetings, and forbidding the universities to teach social sciences. The Communist government also used censorship, restricting political freedom. | The two regimes treated the wealthy aristocrats differently. Even after the emancipation of the serfs, aristocrats were favoured - the serfs were forced to pay high redemption payments (the serfs had to pay money for the land they were allocated). Aristocrats held over 90% of the country's wealth. However, the Communists wanted to create a more equal society. Lenin believed that the proletariat (the working class) along with the peasantry would overthrow the bourgeoisie. When Lenin was in power, the members of the bourgeoisie were actively arrested by Cheka. |

Military | Peasants conscripts were the core of Imperial Russia military power. While the USSR participated in a mechanised military that surpassed the one of Imperial Russia. | |

Geography | Both regimes controlled a vast territory. | Soviet Russia was much larger than Imperial Russia. Imperial Russia stretched from Central Europe to the Pacific Ocean, Finland, Poland, Armenia, and Georgia also fell to its borders. However, new Soviet Socialist Republics entered the USSR by 1940: Karelia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union had several client states that were militarily, politically, and economically dependent on the USSR. The client states were the Warsaw Pact nations. |

The Tsarist regime ended in 1917, following the Bolshevik takeover of Russia. Tsar Nicholas II was the last of the Russian tsars and was executed on 17 July 1918.

Both tsarist and communist Russia had highly centralised control of governance. They both used various levers of repression to bend people to their will and were highly dependent on individual leaders for the success or failure of the state.

The tsars were the rulers of the Russian empire. The Tsars were also head of the Orthodox Church, which meant that they had a divine right to rule over the empire and had complete authority over every aspect of governance. The tsarist regime refers to the autocratic rule by the tsars.

Tsar was a title given to the emperors of Russia before the Russian revolutions of 1917. In medieval times, the term meant a supreme ruler, who was also the head of the Orthodox Church. The term tsarist typically refers to the time period in which Russia was ruled by Tsars.

Who was the last Tsar of the Russian Empire?

Nicholas II

When did Alexander II enact the emancipation of the Serfs?

1861

Give three (of four) reasons for Russia’s slow economic development

Any three of the following:

Inhospitable terrain

Extreme climate

Size and communication

Serf-based economy

Give two examples of freedoms that Serfs lacked.

Any two of the following:

Could be bought and sold

Could be punished without trial

Needed their owner's permission to marry

Eligible for conscription into the army

When was the Crimean War?

1853–56

What was Lenin’s slogan during the 1917 October Revolution?

Peace, Land, and Bread

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in

Already have an account? Log in

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Already have an account? Log in