Want to get better grades?

Nope, I’m not ready yetGet free, full access to:

- Flashcards

- Notes

- Explanations

- Study Planner

- Textbook solutions

Crime has a long history in human society. Just as Willhelm Wundt is considered the father of psychology, Hugo Münsterberg is considered to be one of the first to bring psychology into the courtroom. Why people commit crimes whilst others forgo a life of crime has interested psychologists for a long time.

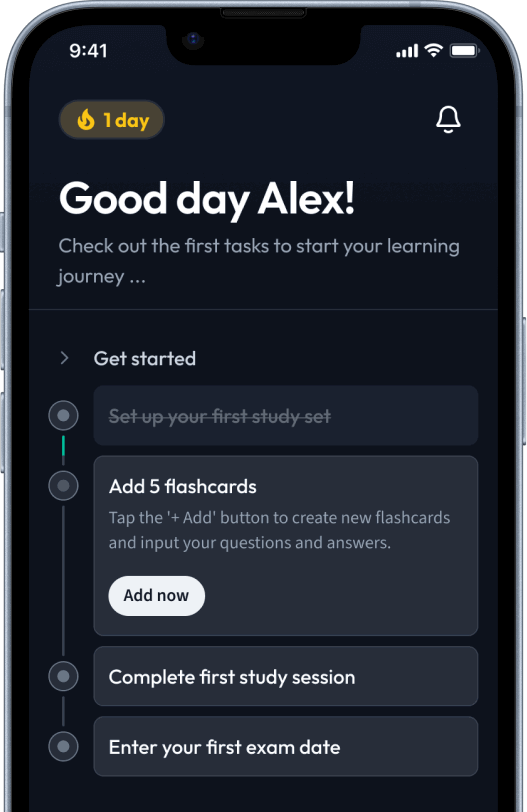

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenCrime has a long history in human society. Just as Willhelm Wundt is considered the father of psychology, Hugo Münsterberg is considered to be one of the first to bring psychology into the courtroom. Why people commit crimes whilst others forgo a life of crime has interested psychologists for a long time.

The need to understand the reasons behind criminal behaviour, how to catch a criminal, and, more importantly, how to prevent crime became obvious. This is where forensic psychology comes in.

Fig. 1 - Forensic psychology explores the theories behind criminal behaviour

Fig. 1 - Forensic psychology explores the theories behind criminal behaviour

Forensic psychology is investigative psychology that looks into the psychological theories behind criminal behaviour. Why a person may commit a crime, who they may be and how they act are all factors psychology explores.

Whilst initially, forensic psychology was not a fully respected discipline (Münsterberg faced scepticism in the courtroom by the judge and others present), it has gained credibility and esteem over the years.

Forensic psychology applies psychology to law and the criminal justice system.

Many television shows focus entirely on forensic psychology procedures. Finding and catching criminals using psychological methods has proven popular amongst the public.

Forensic psychologists typically help in the cases of eyewitness testimonies, assessing competency to see if a person is in a sound state of mind to stand trial and help decide appropriate treatment plans and sentencing.

Crime is an act that violates the law, usually resulting in punishment. What people consider a crime varies from place to place (culture, setting, and time can change the definition of a crime).

Whilst certain acts are illegal across the board (murder, for example), other crimes, such as drug use and theft, may incur different degrees of punishment.

It's important for governing bodies to know the true extent of crime rates, and one way to do this is through measuring crime.

Measuring crime rates comes in three forms, mainly:

Offender profiling focuses on accurately predicting the characteristics of unknown criminals through various procedures and is an investigative tool, a core aspect of investigative psychology. There are two main forms of offender profiling: the top-down and the bottom-up approaches.

The top-down approach is used by America, whereas the British use the bottom-up approach.

Developed by the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation), the top-down approach classifies criminals into different types, working from the top down. Using data from 36 convicted serial killers and murderers (including the infamous Ted Bundy), the FBI identified organised and disorganised groups.

The top-down approach assumes that criminals show particular behaviours (often known as their modus-operandi or ‘MO’).

The FBI follow four steps when creating profiles (Douglas et al., 1986):

Fig. 2 - America uses the top-down approach in offender profiling.

Fig. 2 - America uses the top-down approach in offender profiling.

Developed by David Canter, the bottom-up approach uses investigative psychology and geographical profiling to identify possible offenders. There are no typologies. Investigators examine crime scenes, analyse evidence, and talk to witnesses to hypothesise about the likely characteristics of the perpetrator, such as:

Investigative psychology includes details from the crime scene that are matched with psychology theories and analysis of offenders to find the most likely match. Geographic profiling examines crime scenes to determine the offender’s base and possible future crimes.

Fig. 3 - The UK uses the bottom-up approach to offender profiling.

Fig. 3 - The UK uses the bottom-up approach to offender profiling.

Several biological explanations and theories for criminality exist in psychology (and criminology), such as the atavistic form, and genetic and neural explanations.

Positivist criminology suggests no free will exists in criminal behaviours; our features decide it. Cesare Lombroso described the atavistic form in 1876, which states that criminals are less evolved people or primitive subspecies unfit for modern society.

Lombroso noted that this criminal subspecies could be identified by specific characteristics such as:

Physical features can indicate criminal tendencies, according to Lombroso.

Psychologists have also tried to find genetic and neural explanations for criminality. Twin studies and candidate genes are essential parts of this process.

Other psychologists claim that there may be neural differences between criminals and non-criminals.

Raine et al. (1997) found that murderers had neural differences in their prefrontal cortex, amongst other notable brain areas. They had dysfunctional brain processes, supporting the neural explanation.

Are murderers born or made? Psychological explanations explore the psychological aspect of offending behaviours, namely identifying issues in the mind of offenders and identifying possible environmental conditions that may explain the behaviours.

Eysenck (1964), a critical exponent of personality and intelligence research, stated that behaviour could be divided into three categories: introversion/extroversion (E), neuroticism/stability (N), and psychoticism (P). According to Eysenck, we inherit the extent and type of character traits through our nervous system, which means that criminality could have a biological basis.

Several explanations for criminal behaviour suggest that offenders think differently than their peers. They show different thinking patterns, levels of moral reasoning, and cognitive distortions that affect their perceptions of reality.

Differential association theory, developed by Sutherland (1939), suggests criminal behaviour is a learned interaction where offenders learn the techniques, methods, and motives of criminal behaviours from other criminals.

According to cognitive theory, criminals also have cognitive biases (information processing errors or biases) that influence their behaviour. Two examples are:

Fig. 4 - There are a variety of psychological explanations for criminal behaviours.

Fig. 4 - There are a variety of psychological explanations for criminal behaviours.

Psychodynamic explanations for criminal behaviour explore offending behaviours through the lens of Freud's theories. Blackburn (1993) suggests that the differential development of the superego can lead to criminal behaviour:

Freud also explored defence mechanisms, namely displacement, repression and denial.

Bowlby (1944) asserts that a child who cannot form a solid attachment to their mother figure is less likely to form meaningful relationships in adulthood and is more likely to develop a personality type of ‘loveless psychopathy’. A lack of guilt, empathy, and feelings for others, all traits associated with criminal behaviour, characterise this personality type.

So, the offender committed a crime. What next? Punishment for criminal behaviour can take different forms, from more traditional versions to modern therapeutic approaches.

Custodial sentencing is when the court orders the offender to serve time in a prison or other closed therapeutic/educational facility such as a psychiatric hospital.

The custodial sentence has many purposes :

It also has many psychological effects:

In this section, we also address recidivism.

Behaviour modification in custody applies the behaviourist approach that attempts to replace criminal behaviour with desirable, productive behaviour by using positive/negative reinforcement.

A clear example of this is the idea of ‘getting out on good behaviour’, where punishment is reduced for inmates as a reward for good behaviour while incarcerated.

Anger management involves a therapeutic program to identify and manage the anger that may have led to criminal behaviour. This process consists of three phases:

Restorative justice focuses on reconciliation between offender and victim. The aim is to enable the offender to understand their crime’s impact and empower victims by giving them a ‘voice’.

Whilst forensic psychology provides multiple techniques to investigate criminal behaviour and identify possible explanations for criminal behaviour, it has problems in itself.

Forensic psychology is investigative psychology that looks into the psychological theories behind criminal behaviour. Forensic psychology applies psychology to law and the criminal justice system.

We can define crimes using official characteristics, victim surveys and offender surveys. Offender profiling focuses on accurately predicting the characteristics of unknown criminals through various procedures and is an investigative tool.

Biological explanations for crime include atavistic forms and genetic and neural explanations.

Psychological explanations of crime include Eysenck’s theory, cognitive explanations, and differential association theory. Psychodynamic explanations for crime include a malformed superego and maternal deprivation theory.

We can treat delinquent behaviour through incarceration, behaviour modification, anger management, and restorative justice.

Forensic psychology can help prevent and explain crime.

Forensic psychology applies psychology to law and the criminal justice system.

Criminal psychologists develop psychological profiles of criminals to understand them or prevent crime. Forensic psychology is investigative psychology that looks into the psychological theories behind criminal behaviour.

Criminal psychologists develop psychological profiles of criminals to understand them or prevent crime. Forensic psychologists look at crime more widely and apply this study to the criminal justice system.

Forensic psychology can help us understand criminal motivations and influences by producing different investigative techniques, such as offender profiling, how to measure crime rates accurately, and exploring different explanations of crime (psychological and biological).

Who proposed differential association theory and when?

Sutherland proposed this theory in 1939.

What does differential association theory state?

People learn to become offenders through interactions with others (friends, peers, family members). Criminal behaviours are learned through other people’s values, attitudes, methods, and motives.

How can the theory explain why crime is more prevalent in certain communities?

Perhaps the people are all learning from each other in some aspect, or the community’s general attitude is ‘pro-crime’.

How can the theory explain why convicts after their release from prison frequently continue offensive behaviour?

Often, in prison, they have learned how to improve their ‘technique’ through observational learning and imitation, or even through direct learning from one of the other prisoners.

What were the six most significant risk factors for criminal activity at age 8–10, according to Farrington et al. (2006)?

What is a strength and weakness of Farrington et al. (2006) study?

The study shows support for differential association theory; however, some of the factors can also be due to genetics.

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in

Already have an account? Log in

The first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Already have an account? Log in