How do we know the diagnostic manuals used in mental health are reliable and valid? Are there ways in which we can improve the reliability and validity of diagnosis and classification in schizophrenia? Both the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) and the ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) require high levels of reliability and validity in diagnosing and classifying schizophrenia.

Reliability and validity in diagnosis in psychology are essential for the DSM and ICD to be effective tools for psychiatrists to diagnose patients.

Schizophrenia is usually diagnosed between the ages of 20 to 30 for both men and women, although symptoms can appear long before then, sometimes even in early childhood.

- First, we are going to discuss reliability and validity in the diagnosis and classification of schizophrenia, defining both validity and reliability.

- We will highlight the Rosenhan (1973) schizophrenia study, delving into the study and how it raised awareness of the issues in the diagnosis and classification of schizophrenia.

- We will go into more detail on the validity of diagnosis in psychology, particularly on how it affects schizophrenia. We will highlight how comorbidity, symptom overlap, and gender and culture bias affect validity.

- Finally, we will summarise other key issues in the reliability and validity of diagnosis and classification in schizophrenia.

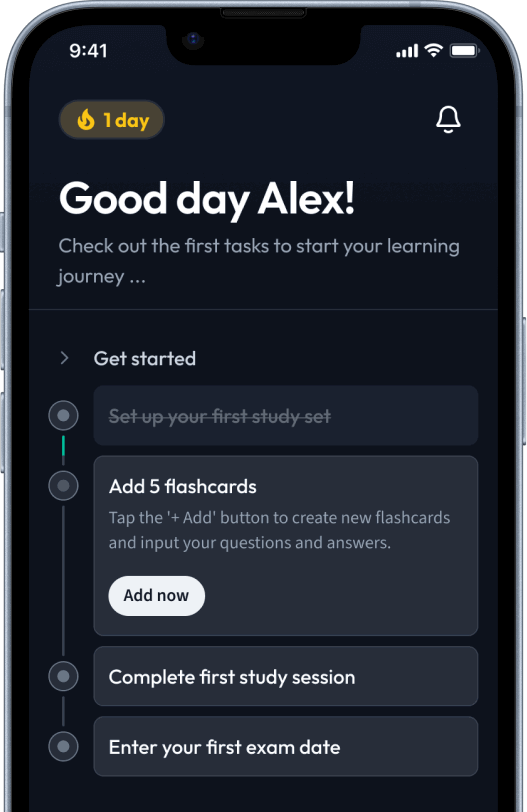

Fig. 1 - Reliability and validity are important aspects of a diagnostic manual.

Fig. 1 - Reliability and validity are important aspects of a diagnostic manual.

How can we Define Reliability in Diagnosis?

Reliability in research refers to the consistency of achieving the same results if different researchers were to perform the same experiment over and over again. A study is considered reliable if it can be repeated and give the same results.

Reliability in diagnosis refers to the level of agreement that different psychiatrists can achieve on a single diagnosis for an individual, both over time and across cultures, provided that the disorder’s symptoms have not changed.

To ensure a diagnosis and its classification are reliable, test-retest reliability is usually measured by the intraclass correlation (ICC) and the inter-rater reliability test, also measured as the kappa score. Both are statistical results that examiners can use to confirm the reliability of their results.

If the kappa classification has a score of 0.7 or more, it is considered reliable.

An Example of Test-Retest Reliability

Let's explore an example of test-retest reliability in schizophrenia tests.

To measure the reliability of something, the test-retest method is often used. In this method, a test is performed twice on one person at two different times.Lee et al. (2011) examined two tests used to measure switched and sustained attention in patients with schizophrenia for test-retest reliability.

- The Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT)

- The Digit Vigilance Test (DVT)

147 Participants were tested with an interval of 1 week between tests. The results indicated both tests had good test-retest reliability and were stable measures. They both had high ICC values, a commonly used measure of test-retest reliability in studies.

An Example of Inter-Rater Reliability

Let's explore an example of inter-rater reliability measures in schizophrenia.

Inter-rater reliability is when different psychiatrists should come to the same conclusion or diagnosis when diagnosing a person. The kappa score is a measure of inter-rater reliability.

In Cheniaux (2009), two psychiatrists assessed 100 patients using the DSM and the ICD. They found that inter-rater reliability was poor, as one psychiatrist diagnosed 26 patients with schizophrenia using the DSM while diagnosing 44 patients with schizophrenia using the ICD.

As a result, schizophrenia is underdiagnosed or overdiagnosed depending on which system is used.

Similarly, Regier (2013) found the DSM edition at that time had a kappa score of 0.45, which is quite low and below the satisfactory requirement of 0.7, indicating a weakness in schizophrenia diagnosis.

Rosenhan (1973) Schizophrenia Study

Rosenhan’s (1973) study, one of the most influential studies affecting the diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders today, highlighted the problems with reliability in the diagnosis of psychiatric disorders. Rosenhan emphasised that psychiatric hospital staff were somewhat desensitised and unaware of how drastic the experience of being admitted as a patient can be.In this study, Rosenhan himself and seven healthy individuals went to 12 different psychiatric hospitals.

- These were three women and five men from various backgrounds, from psychologists to a painter. They used pseudonyms.

The pseudopatients asked the hospitals for an appointment and then complained upon arrival that they heard unfamiliar but same-sex voices, specifically:

These words were explicitly chosen to show the pseudopatient has symptoms such as hallucinations, and to suggest that the pseudopatient believes their life is ‘empty and hollow’.

- The pseudopatients falsified their name, occupation, and profession to protect their identity. However, they were free to talk about their history and circumstances and were asked to present events from their life story as if they had happened.

Their history showed no signs of pathological problems.

Once admitted, the pseudopatients immediately ceased all symptomatic behaviours. They behaved as they normally would and talked to other patients and staff as they would before they were admitted as pseudopatients. They were not told when they could leave the clinic. Instead, they were told they would have to convince the staff that they were sane to leave the clinic.

Pseudopatients who were asked how they were doing told staff they were fine and no longer had symptoms. They behaved accordingly and followed the rules. They also noted observations about the hospitals, secretly at first, but when it was obvious that no one cared or took note, they wrote them down without secrecy.

Fig. 2 - In Rosenhan's study, patients behaved normally after entering the hospital.

Fig. 2 - In Rosenhan's study, patients behaved normally after entering the hospital.

All but one of the patients were discharged with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in remission. Their length of stay ranged from 7 to 52 days (an average of 19 days). They were not classified as ‘sane’; the label of schizophrenia remained. The pseudopatients were not detected during their stay, although they remained sane throughout. There was a lack of adequate observation, but Rosenhan attributes this to a failure of the hospital rather than the patient and the lack of opportunity.

Interestingly, actual patients at the hospital recognised the pseudopatients as sane. About 35 of 118 patients recognised the sanity of the pseudopatients and even suggested their real occupation:

- ‘You are not crazy. You are a journalist or a professor. You are checking out the hospital.’

Patients were more likely than staff to recognise normality, even though the pseudopatient insisted he was sick.

Rosenhah suspects this failure to recognise sanity is due to type 2 errors, also known as false-positive diagnoses. Rosenhan explained that diagnoses in this area of health care are neither useful nor reliable and represent a depressing and frightening reality that we must combat. Hospitals of this type cannot identify and treat these behaviours, and they also convey a sense of powerlessness.

Rosenhan stated:

We now know that we cannot distinguish sanity from insanity.¹

The study impacted the way we treat patients with mental disorders today. It led to a condemnation of the use of institutionalised hospitals and a focus on care in the community.

Validity in Classification and Diagnosis of Schizophrenia

Validity is the legitimacy of a test, i.e., whether what the psychiatrist uses to diagnose a person measures what it purports to measure.

If it is valid, the diagnosis represents something real and is different from other disorders.Cronbach and Meehl (1955) established several types of validity.

Construct validity – one can determine if a measurement instrument represents what it intends to measure.

Content validity – the test represents all construct areas, i.e., all areas of what one measures.

What are the Issues with Validity and Reliability when Diagnosing and Classifying Schizophrenia?

The following issues cause problems with validity and reliability:

- Comorbidity

- Symptom overlap

- Gender bias

- Culture bias

What is Comorbidity?

Comorbidity can be a problem in any type of disorder, but what exactly is comorbidity?

Comorbidity is when two or more disorders coincide in a person.

It is not to be confused with symptom overlap.

Fig. 3 - Comorbidity in schizophrenia can be a common problem in diagnosis.

Fig. 3 - Comorbidity in schizophrenia can be a common problem in diagnosis.

If two disorders can occur in one person, the validity of the diagnosis begs the question, who is to say that it is only one disease and not several?Unfortunately, in the case of schizophrenia, there are many comorbidities with disorders such as OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) and depression. As a result, there are significant problems with the disorder’s validity.Buckley et al. (2009) found that comorbid depression occurs in 50% of patients with schizophrenia.

This finding raises some concerns:

Is it because psychiatrists or diagnostic manuals are poor at recognising the difference between these two disorders?

If they are so similar that there are problems with comorbidity, why can not they be considered a single disorder?

Since there is no truly distinct disorder, it can be difficult to diagnose and treat schizophrenia with confidence.

Symptom Overlap

As there are an abundance of symptoms in schizophrenia as well as other mental health disorders, diagnosis and classification can be tricky.

Symptom overlap is the significant overlap between the symptoms of schizophrenia and other disorders.

Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are good examples.Bambole et al. (2013) noted that patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have both positive and negative symptoms, making it difficult to distinguish between them.If these two disorders have too many symptoms in common, it questions the validity of the classification system and thus the validity of the diagnosis.For example, if a patient has these symptoms:

Avolition

Delusions of grandeur

The ICD may diagnose schizophrenia, while the DSM suggests bipolar disorder, indicating an apparent problem in the way these manuals claim to measure a disorder, and, therefore, a weakness in their validity.

Gender Bias in Diagnosing and Classifying Schizophrenia

Gender bias is problematic in many areas of research, and it is not exempt from psychological research.

Gender bias in the classification and diagnosis of schizophrenia occurs when the diagnosis is dependent on the patient’s gender. What symptoms they display and explain is usually irrelevant, as judgments are made based on their gender.

There may be gender-specific criteria, or there may be a bias based on stereotypes that the clinician believes in.

In the study by Loring and Powell (1988), 290 male and female psychiatrists were presented with two case studies of patient behaviour. When the patient was described as male, 56% of them were diagnosed with schizophrenia. However, only 20% diagnosed the patient as schizophrenic when described as female.There was a clear gender bias, but it was not present in the female psychiatrists when they made the diagnosis, suggesting that the gender of both the patient and the psychiatrist is a factor.

Longenecker (2010) found that more men than women have been diagnosed with schizophrenia since 1980.Are men genetically more prone to schizophrenia? Or do women function better in their daily lives than men with the disorder? If women present with the same symptoms but cope better because they have more support or continue to work and maintain relationships, there could be a bias among treating physicians and underdiagnosis in women.

Cotton et al. (2009) hypothesised that women cope better with their symptoms because they function better and may have more support. They function better on an interpersonal level and may not be diagnosed where men would be diagnosed with similar symptoms.Better interpersonal functioning may lead psychiatrists to underdiagnose women because the symptoms are masked and buried under-functioning routines. Some thus believe the case is too mild for a specific diagnosis, even though men would have been diagnosed with the same level of symptoms.

Cultural Bias in Diagnosing and Classifying Schizophrenia

Cultures differ across the world, and research has long had issues with the generalisability of data because of this.

Fig. 4 - Culture across the world differ in their approaches to diagnosing schizophrenia, flaticon.com/authors/flat-icons

Fig. 4 - Culture across the world differ in their approaches to diagnosing schizophrenia, flaticon.com/authors/flat-icons

Cultural bias exists because some psychiatrists diagnose a patient differently if the patient is from a different cultural background. They judge the patient according to what they think is acceptable in their own culture, rather than looking at the patient objectively and considering the patient’s culture and what is acceptable in the patient’s cultural views.

Tortelli et al. (2015) noted that despite improved study methods over time, there has been a higher rate of psychotic disorders in Black Caribbean ethnic groups in England over the past 60 years.

Ineichen et al. (1984) suggested people of West Indian origin were overdiagnosed with schizophrenia when assessed by White doctors in Bristol, possibly due to their ethnic background and culture.

Minsky et al. (2003) found that African Americans were more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenic disorder than Latinos and European Americans.

Copeland (1971) also found that when a large group of psychiatrists from the US and the UK were presented with descriptions of a patient who exhibited certain behaviours and symptoms, American psychologists used a much wider variety of clinical conditions than British psychologists, often overdiagnosing them in comparison.

Why is that so?

There may be a cultural problem with understanding what is ‘normal’ behaviour because in some cultures. In Africa, hearing voices and doing things that are normally considered positive symptoms of schizophrenia are more accepted than in other cultures where this is considered bizarre and irrational.

Racial biases could also play a role. When certain ethnic minorities are overdiagnosed compared to White people, especially by White psychiatrists, it indicates a high degree of miscommunication, bias, and lack of understanding of the patient and their symptoms.

Since countries of origin generally do not support these high diagnosis rates, there is no genetic susceptibility. Why are African Americans in another country more likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia than people in Africa and the West Indies?

Reliability and Validity of Classification and Diagnosis of Schizophrenia

In light of the above, it is also important to acknowledge that:

- No objective test for schizophrenia exists, as there is no biological basis to assess it. It can only be diagnosed by clinical interview, leading to the abovementioned problems. If bias and lack of reliability and validity exist, schizophrenia cannot be diagnosed with certainty.

- When people are misdiagnosed, several problems arise, especially because schizophrenia has a stigma attached to it. Angermeyer and Matschinger (2003) surveyed adults of German nationality and found that labelling people with schizophrenia has a strong negative impact on public opinion.

- In the case of misdiagnosis, treatment is likely to be ineffective because it does not address the root cause and does not properly treat symptoms.

Reliability and Validity in Diagnosis and Classification of Schizophrenia - Key takeaways

- Reliability and validity are both key components of classification and diagnosing systems in psychology and are synonymous with successfully identifying and treating a person.

- Reliability is the degree of agreement different psychiatrists can achieve on a single diagnosis for an individual, both over time and across cultures, provided the disorder symptoms do not change. It is about consistency and being able to repeat results across different tests. Test-retest and inter-rater reliability tests ensure reliability.

- Rosenhan (1973) demonstrated how diagnoses of mental disorders are neither useful nor reliable in his study, where he and seven pseudopatients entered a hospital feigning hallucination symptoms but immediately behaved sanely upon entry.

- Validity is about the legitimacy of a test, whether what the psychiatrist uses to diagnose a person measures what it claims to measure.

- Problems with validity occur when there are issues with comorbidity (two or more conditions within a person), symptom overlap (overlapping symptoms in a person across multiple conditions), gender bias, and cultural bias.

References

- Rosenhan, D. L. (1973). On Being Sane in Insane Places. Science, 179(4070), 250–258. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.179.4070.250

Explanations

Exams

Magazine